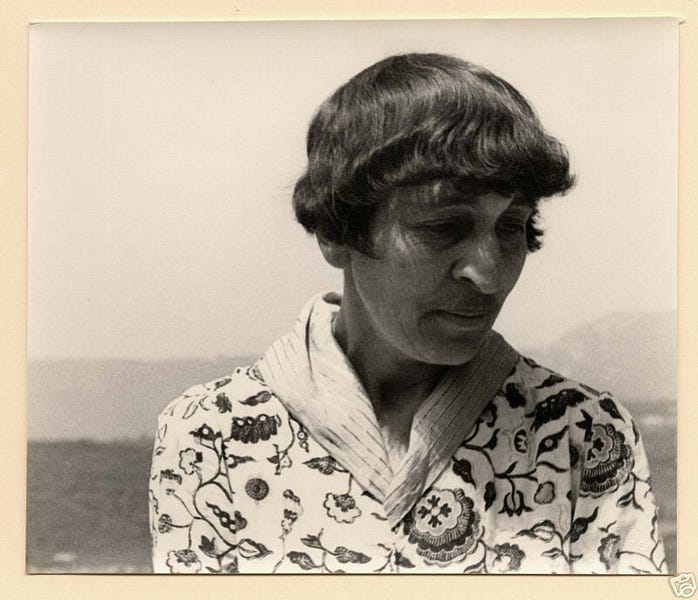

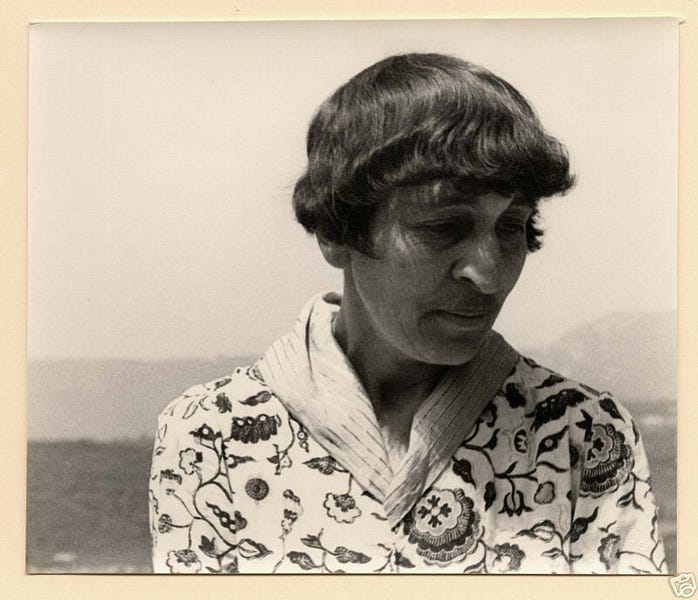

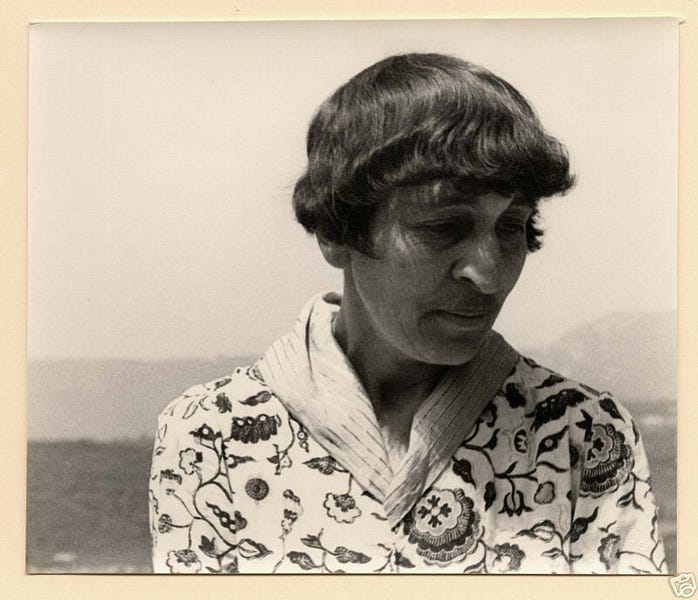

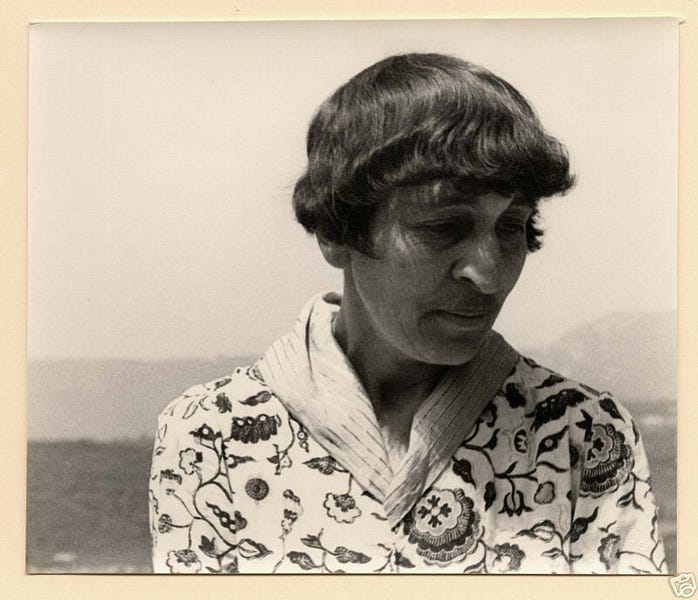

Looking for Alice

Metadata

Highlights

- But when Gertrude Stein declined to label her desire as lesbian, she was, as I understand it, saying something like this: thinking in categories would interfere with my ability to freely pattern-match for the particular type of individual I resonate with.

Some people think Stein was lying when she said she wasn’t lesbian. And they are disappointed by that. (The fact is that most people Stein liked happened to be gendered like Alice.) But hers is the right attitude: you do not like a category. You like individuals. And you’re not born knowing which kind.

So what do you do? You go talk to a thousand people (increasingly less randomly sampled) and see if there are any patterns in who makes you feel excited and alive and true and heard. And then you start hanging out with people like that. (View Highlight)

- Anyway. There is a trope in romance that when you meet the person you are supposed to be with, you can talk about anything. You can apparently inverse that too: if you talk about anything that pops into your mind, you can tell if you’re supposed to be with the person by judging their reaction. Most “dates” would have been hurt by my monologue that night, or bored, or appalled. Johanna’s reaction was more something like: I’ve never met anyone who takes his thoughts so with such loving seriosity, and he’s apparently not at all ashamed of his pain. I wish I felt like that about my pain. Also, I need to talk about ideas like this. (View Highlight)

- The type of person I’m assuming we’re looking for here is 1) someone that you will find fascinating to talk to after you’ve talked for 20,000 hours, 2) you feel comfortable with them talking through the hardest and most painful decisions you will face in your life, and 3) the conversation is wildly generative for both of you, in that it brings you out, helps you become.

That is a very particular kind of conversation. You want to sample it as soon and as much as possible. (View Highlight)

- “Please describe an encounter with a squirrel.”

Lopez is a bit surprised by the question, but he takes it in a playful spirit—his voice lifts, joyously. He starts to talk faster. (This is where the conversation shifts into the type you want.) He is no longer saying versions of things he has said before, he’s not protecting himself, he’s just there.

From that point on, it takes about ten seconds before he’s crying.

In interviews, Herzog likes to mention this conversation to explain his craft. “But how on earth did you know to say that?” says the interviewer. “Were you just trying to say something unexpected to unbalance him?” “No, it was not random”, Herzog says. “I knew I had to say those exact words. Because I know the heart of men.”

This is to a certain extent true—finding a question that good under time pressure is remarkable—but it is also fairly trivial to do what he did. If you want to prompt someone to be authentic and playful and generative, you usually just need to ask them something where they have a rich experience to pull from but have never pulled an answer from that experience before. If you ask two or three increasingly detailed questions about something they tell you, you get there. (View Highlight)

- When you enter this strange and unstable realm of conversation, you get a lot of information rapidly. I tend to find that almost everyone is captivating and loveable when I manage to talk like this. But when I do it with Johanna—especially in the first few years—it was like my entire mental landscape broke apart and all was possibility and flux. As Philip Glass says about his mentor, Nadia Boulanger, “it was like having a brain transplant”.

That open conversational space, which is the heart of our relationship, is not something I can explain; it is not something I knew I was looking for; I’m not even the same person after having been there. It does not look anything like I imagined a relationship would or should look. (View Highlight)

- When you talk about people you like, or rather when you talk about that thing that happens between you—you have to transform a very complex impression into a string of words. Some relationships can easily be compressed into a compelling string of words. This is usually because they conform to some sort of trope of how romance should look. In my experience, great relationships are harder to compress into a sensible string of words. (View Highlight)

Looking for Alice

Metadata

Highlights

- But when Gertrude Stein declined to label her desire as lesbian, she was, as I understand it, saying something like this: thinking in categories would interfere with my ability to freely pattern-match for the particular type of individual I resonate with.

Some people think Stein was lying when she said she wasn’t lesbian. And they are disappointed by that. (The fact is that most people Stein liked happened to be gendered like Alice.) But hers is the right attitude: you do not like a category. You like individuals. And you’re not born knowing which kind.

So what do you do? You go talk to a thousand people (increasingly less randomly sampled) and see if there are any patterns in who makes you feel excited and alive and true and heard. And then you start hanging out with people like that. (View Highlight)

- Anyway. There is a trope in romance that when you meet the person you are supposed to be with, you can talk about anything. You can apparently inverse that too: if you talk about anything that pops into your mind, you can tell if you’re supposed to be with the person by judging their reaction. Most “dates” would have been hurt by my monologue that night, or bored, or appalled. Johanna’s reaction was more something like: I’ve never met anyone who takes his thoughts so with such loving seriosity, and he’s apparently not at all ashamed of his pain. I wish I felt like that about my pain. Also, I need to talk about ideas like this. (View Highlight)

- The type of person I’m assuming we’re looking for here is 1) someone that you will find fascinating to talk to after you’ve talked for 20,000 hours, 2) you feel comfortable with them talking through the hardest and most painful decisions you will face in your life, and 3) the conversation is wildly generative for both of you, in that it brings you out, helps you become.

That is a very particular kind of conversation. You want to sample it as soon and as much as possible. (View Highlight)

- “Please describe an encounter with a squirrel.”

Lopez is a bit surprised by the question, but he takes it in a playful spirit—his voice lifts, joyously. He starts to talk faster. (This is where the conversation shifts into the type you want.) He is no longer saying versions of things he has said before, he’s not protecting himself, he’s just there.

From that point on, it takes about ten seconds before he’s crying.

In interviews, Herzog likes to mention this conversation to explain his craft. “But how on earth did you know to say that?” says the interviewer. “Were you just trying to say something unexpected to unbalance him?” “No, it was not random”, Herzog says. “I knew I had to say those exact words. Because I know the heart of men.”

This is to a certain extent true—finding a question that good under time pressure is remarkable—but it is also fairly trivial to do what he did. If you want to prompt someone to be authentic and playful and generative, you usually just need to ask them something where they have a rich experience to pull from but have never pulled an answer from that experience before. If you ask two or three increasingly detailed questions about something they tell you, you get there. (View Highlight)

- When you enter this strange and unstable realm of conversation, you get a lot of information rapidly. I tend to find that almost everyone is captivating and loveable when I manage to talk like this. But when I do it with Johanna—especially in the first few years—it was like my entire mental landscape broke apart and all was possibility and flux. As Philip Glass says about his mentor, Nadia Boulanger, “it was like having a brain transplant”.

That open conversational space, which is the heart of our relationship, is not something I can explain; it is not something I knew I was looking for; I’m not even the same person after having been there. It does not look anything like I imagined a relationship would or should look. (View Highlight)

- When you talk about people you like, or rather when you talk about that thing that happens between you—you have to transform a very complex impression into a string of words. Some relationships can easily be compressed into a compelling string of words. This is usually because they conform to some sort of trope of how romance should look. In my experience, great relationships are harder to compress into a sensible string of words. (View Highlight)